In February, the government of Alberta signed a ten-year framework agreement with the Métis Nation of Alberta, emphasizing a relationship based on recognition, respect, and cooperation. In March, Alberta and the Blackfoot Confederacy signed a protocol agreement on how they will work together on economic development and other areas of concern to both parties. These agreements, of course, are only two of many instances of Indigenous people in the mainstream media recently.

In December and January, the government of Canada faced challenges from Indigenous youth and leaders on pipeline development. And in January, actress Jane Fonda came to Alberta in solidarity with Indigenous political leaders to express concern over the oil industry, new pipeline developments, and the irreparable environmental destruction to the boreal forest and waters in Indigenous traditional territories where the oil sands industry operates.

Chief Allan Adam of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation expressed disappointment that the Alberta government is still approving new oil projects and that his “people are still being diagnosed with cancer at an alarming rate … [Neither] the federal [nor] the provincial government has done anything [in] regards to a health study that we keep lobbying for. Nor does industry want this health study to commence.”

In February, Indigenous people also made news with a court decision that finds Canada liable for harm caused by the removal of Indigenous children from their homes between 1965 and 1984 and placed in non-Indigenous care, and again regarding frustration over delays to begin the process of an inquiry into Canada’s missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. In March, many publicly expressed outrage at a Canadian Senator’s comments that residential schools were “well-intentioned.”

These events and contestations are all happening roughly a year after the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report. As a result of decades of work by Indigenous political leaders, lawyers, educators, and activists, Indigenous rights and issues seem to be gaining increasing recognition in provincial and federal politics, economics, and the courts.

In Alberta, where resource extraction is a factor in many areas of political, economic, and everyday community relations, it is important to understand how Indigenous rights and issues interact with the oil industry and the provincial government, especially given the power and influence the industry has in the province.

In this blog, we discuss 10 key facts that all Albertans should be aware of as we work to understand and evaluate these ongoing events.

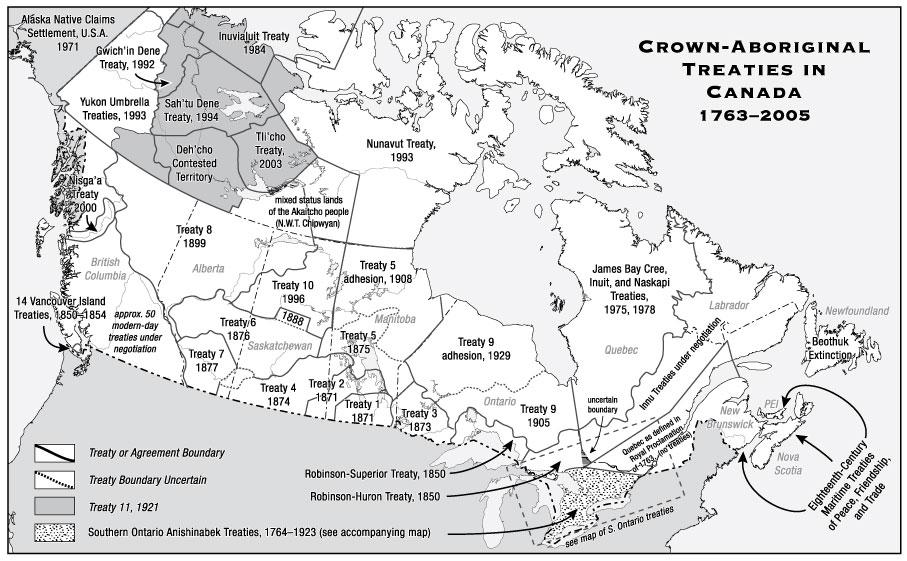

1. We are all treaty people

All Canadians—settlers and Indigenous peoples alike—are treaty people. Although settlers (individuals who are not Indigenous) may not always be cognizant of it, treaties in Canada apply to everyone in the country. The treaties detail promises, obligations, and benefits of both Indigenous and settler populations with regard to the coexistence of both populations on land traditionally occupied by Indigenous peoples. There are three treaties in Alberta which include 45 First Nations:

- Treaty 6 was signed at Carlton and Fort Pitt in 1876 and covers central Alberta and Saskatchewan. It is home to 16 Alberta First Nations.

- Treaty 7 was signed at the Blackfoot Crossing of Bow River and Fort Macleod in 1877 and covers southern Alberta. It is home to five Alberta First Nations.

- Treaty 8 was signed at Lesser Slave Lake in 1899 and covers portions of Northern Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and part of Northwest Territories. It is home to 24 Alberta First Nations.

Image source: Southern Chiefs Organization

The above map illustrates historical treaties dating from 1763 to 2005. More contemporary agreements referred to as modern treaties continue to be negotiated in areas without previously settled claims. However, the modern treaty negotiation process has been stalled as of late, and some British Columbia First Nations which have not signed treaties are questioning whether treaties are the best route for advancing their rights in light of recent court decisions on Indigenous rights and title.

2. About 23,000 Indigenous people live in Alberta’s oil sands region

Six percent of Alberta’s total population is Indigenous, and approximately 23,000 Indigenous people from 18 First Nations and six Métis settlements live in Alberta’s oil sands region.

Image Source: Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers

A 2016 CBC publication discusses an unreleased government report that finds the government of Alberta is failing Indigenous peoples in the oil sands region, specifically with negative repercussions to their land, rights, and health as a result of industrial development in the region. The article describes the report as “damning,” pointing to the prioritization of economic interests over traditional land use, the violation of treaty rights, and claims by Indigenous communities that the Lower Athabasca Regional Plan was being used against their interests.

The detrimental health effects of oil sands development for Indigenous people is not a new topic in Alberta political discussions. An Edmonton Journal video from 2010 engages Indigenous people in Fort Chipewyan about the heightened rate of deaths by cancer in the community and how these deaths are seen to be a direct result of the pollution of the land, air, and wildlife by industrial activity. When Indigenous people living in areas close to industry engage in their traditional lifestyles of living off the land, including consuming wildlife, they are at heightened exposure to pollutants in the ecosystem. However, these concerns don’t seem to be taken seriously by oil corporations and the provincial and federal governments.

3. A long history of colonialism has deeply shaped the relationship between First Nations and the state in Alberta and across Canada

Land settlements in Western Canada were initially completed for the sake of creating stability for industry to move in (Slowey & Stefanick, 2015). The widespread systemic racism Indigenous peoples and communities still face in Alberta and across Canada is rooted in the colonial past and present, and these colonial relations undergird the development and current operations of the oil and gas industry in the Prairies and British Columbia.

In BC, for example, until its recent electoral defeat, Christy Clark’s fossil-fuel-industry-friendly Liberal government and extractive industries—not just fossil fuels, but them in particular—had been anxious for greater “certainty” about Indigenous rights and title in relation to proposed developments, and was driving the push to make deals. The BC Liberal government’s enthusiasm in recent years to make more deals with First Nations to enable further resource extraction is a contemporary extension of the colonial development model, but in a somewhat more accommodating form.

The process of colonization created incredible inequalities and inequities for Indigenous peoples, seen manifesting today in intergenerational trauma related to drastically heightened levels of incarceration of Indigenous individuals, breakdown of Indigenous families as Indigenous children are taken into the care of inadequate welfare systems, under-employment of Indigenous peoples, reduced access to basic human and citizenship rights including education, health care, safe water, housing, and an epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (Alook, 2016).

Ongoing efforts, such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, attempt to recognize the problematic past and present of the Canadian nation-state. It is promising that February’s agreement between Alberta and the Métis Nation of Alberta emphasizes a nation-to-nation approach, however, more telling will be in how this agreement and other related issues continue to unfold.

4. Indigenous scholars emphasize the fundamental differences between dominant Western and Indigenous forms of knowledge

A 2010 publication by Parkland Institute, As Long as the River Flows: Athabasca River Use, Knowledge, and Change, illustrates the connectedness of Indigenous peoples with the land and the water, pointing to how their unique relationship with these ecosystems provides an opportunity to observe subtle, incremental changes over time that, as they add up, may be indicative of significant changes to the land and water.

For example, traditional land use practices include spending a great deal of time on the land hunting, trapping, and fishing. When the land, waterways, and wildlife change, it is Indigenous people who are in the best position to observe these changes. When Indigenous people’s health conditions change in specific patterns in line with their location and their traditional land use practices—such as increased rates of specific forms of cancer in communities close to or downstream from oil industry activity—Indigenous people are well-positioned to observe those changes as well.

The Parkland Institute report focuses on community knowledge of the Athabasca River in the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and the Mikisew Cree First Nation, discussing how the river and its tributaries have changed in recent decades, emphasizing concern over lower water levels and reduced water quality. The report is an attempt to translate treaty rights and cultural needs into a form that can be readily applied to policy and decision-making in the region, demonstrating a recognition of the need to translate Indigenous knowledge into a format more digestible to Western-trained policymakers and representatives of industry and government.

One of the recurring themes in Indigenous scholarship is the emphasis on relationality among various Indigenous peoples both within and beyond Canada. Immutable relationality between land, people, and other creatures is fundamental to the worldviews of Indigenous people around the globe but is generally not present or well-understood by Western scholars and educators.

Throughout her career, world-renowned Indigenous scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith has been studying the important differences between Indigenous and Western knowledge, including the Western notion of the individual as a basic unit of society compared to Indigenous understandings of individuals as members of the community, where communal ownership and membership is prioritized over the individual.

Unfortunately, Western knowledge is almost always positioned above Indigenous knowledge in hierarchies of knowledge. This means that Indigenous concerns are not often taken seriously, because the knowledge that those concerns are based on is devalued since it diverges from the dominant Western model of knowledge. This Eurocentric hierarchy of knowledge underpins the systemic racism Indigenous people continue to experience across Canada and other settler colonial states, such as the United States, Australia, and Aotearoa/New Zealand.

5. Impact assessments used to evaluate oil development proposals often present insufficient empirical evidence and have difficulty incorporating concerns and knowledge of Indigenous people

Impact assessments required for new oil industry developments are one area where differing knowledge systems are not functioning well together.

A 2013 article by social scientist Clinton Westman that includes case studies of multiple impact assessments explores the importance of traditional land use for Indigenous peoples, and the difficulty of formal impact assessments to account for this. Westman explains that impact assessments are a tool used to make claims about the future, often with an insufficient basis in empirical evidence.

Westman analyzes assessments that posit benefits to projects but do not include sources or calculations upon which they’ve based their claims. One assessment in his study claims that a project will benefit Indigenous people by improving fishing in the area once it is reclaimed because people will be able to fish in “pit lakes,” despite the fact that other sources indicate concern over fish tainting.

Westman’s research shows that impact assessments have difficulty incorporating the concerns raised by Indigenous peoples about their lived experiences and practical relationship with the land. These assessments generally avoid topics that are not readily rendered into technical understandings, meaning that topics outside those boundaries are overlooked, including spiritual, cosmological, and existential understandings that form the basis of Indigenous cultural traditions and practices, including fundamental relationships between people, the land, and wildlife. These understandings differ from traditional Western ideas about spirituality and how individuals exist in the world and are important elements of evaluating potential impacts of oil industry projects.

When assessors do not possess an in-depth understanding of Indigenous cultures and practices, they are unable to make educated and appropriate assessments about the impacts on those cultures and practice from potential oil industry activity in the future. Through the use of technical concepts and discourse, impact assessments serve as blueprints for the allocation of political and natural resources; politics and rights (including treaty rights) generally do not factor in.

These assessments then, which are a crucial part of adjudicating potential new oil industry developments, are inadequate to truly assess impacts and to appreciate the gravity of these impacts on Indigenous people and their traditional land use practices.

6. Education and career pathways for Indigenous youth need to improve

Although one of the priorities of the framework agreement signed between Alberta and the Métis Nation of Alberta is to increase economic opportunities to enhance individual and community well-being through numerous avenues, including increasing educational achievement as well as increased employment training, a troubling history of problematic arrangements between Indigenous communities, the state, and industry casts a shadow over the process of developing new arrangements.

A 2009 report by Alison Taylor, Tracy Friedel, and Lois Edge of the University of Alberta’s Department of Educational Policy Studies examines the pathways for First Nation and Métis youth in the oil sands region. The report finds that although Indigenous peoples in the region have improved educational attainment and employment opportunities compared to Indigenous peoples elsewhere in the province, they are still lagging behind in educational achievement and career opportunities when compared to non-Indigenous people in the region.

The authors explain that there is no shortage of policies and programs targeting Indigenous education and job training, however the outcomes are not reflective of the investments. This is because Indigenous people face undue challenges in terms of a lack of quality education from primary school upwards, additional challenges for Indigenous youth who have to leave their communities to attain education, heavy involvement of industry that can lead to fragmentation of education and training, and the limited control Indigenous communities have over education in the region.

The pathways report finds that Indigenous youth are often streamed out of the provincial school system and into the labour market, specifically into unskilled or semi-skilled contract work that does not require a diploma. The lack of a diploma is then a significant barrier to future career opportunities with large industrial employers. The report concludes that the time commitment, expense, and absence of guaranteed employment afterwards may be a disincentive for Indigenous youth to return to school to upgrade their education.

7. Indigenous youth are a growing population with important future workforce implications

Indigenous youth are the fastest growing population in Alberta. This population could be a major human resource, which is useful in a province where we often see labour shortages. The 2016 Alberta Labour Force Profile of Indigenous People found that the proportion of Indigenous people aged 15–24 was 23.7% and those aged 25–54 was 58.1%. The corresponding shares of all Albertans were 15.2% and 55.6%, respectively, in 2016.

8. Public-Private Partnerships (P3s) aren’t the way to finance economic development in Northern Alberta

In the final decade of the 44-year Alberta Progressive Conservative dynasty, public-private partnerships (P3s) increasingly became the preferred model for financing economic development in Northern Alberta. After its 2015 rise to power, the NDP has begun to move the province away from P3s toward more publicly financed capital projects.

PPP Canada describes P3s as “a long-term, performance-based approach to procuring public infrastructure that can enhance government’s ability to hold the private sector accountable for public assets over their expected lifespan.”

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) is more critical of P3s. The CCPA argues that although public-private partnerships are often touted as lowering risk and cost to the public, they in fact do the opposite, but the complexity and misleading accounting of P3s muddies that reality.

The CCPA shows many P3s drastically exceed costs and do not achieve expected returns. This research also demonstrates that the private sector does not better manage risk, and that risk cannot ever be transferred to private businesses because it’s the government that is ultimately responsible for providing public services and infrastructure. The CCPA concludes that P3s are not only concerning for the public, but also negative for the economy.

A 2011 study by social scientists Alison Taylor and Tracy Friedel analyzed the relationship between government, private business, and Indigenous communities by focusing on P3s aimed at economic development in Northern Alberta. Taylor and Friedel explain that P3s aimed at increasing economic well-being and employment opportunities are sold on notions of equality and cooperation. In practice, however, P3s are often more associated with the suppression of alternative forms of education and training, growing inequities within and among Indigenous communities in the area, and generally a lack of government accountability to those communities.

9. Most Indigenous people in Alberta are educated, employed, and urban

Indigenous people in Alberta increasingly live in urban areas. In 2016, Edmonton had the largest portion of the off-reserve Indigenous population at 38.7% of all Indigenous people living off-reserve in Alberta, followed by Calgary at 17.8%.

The 2016 Alberta Labour Force Profile of Indigenous People finds that 43.8% of Alberta’s Indigenous labour force living off-reserve has completed a post-secondary education. Related to point number six above, this is in part a story of inequity in educational access for urban/off-reserve Indigenous people compared to those in rural areas or reserves. Although, many Indigenous people who currently live in urban areas had to move from rural communities and reserves as teenagers or adults to access educational and employment opportunities.

The average employment rate for Indigenous people living off-reserve in 2016 was 60.6%, compared to the general Alberta employment rate of 66.8% (the government of Alberta doesn’t produce on-reserve labour force statistics). Indigenous men had a higher employment rate than Indigenous women in 2016 at 65.9% and 55.5%, respectively. The Canadian labour force participation rate in January 2017 was 65.9%.

A 2016 report by Natural Resources Canada sees major oil sands corporations Suncor, Syncrude, and Shell boasting to have spent between $2.5 and $1.7 billion on contracts with Indigenous-owned contractors and businesses. Notably absent from the Natural Resources Canada report are data on the number of Indigenous people employed directly by Alberta oil producing corporations and what types of jobs Indigenous people work in the industry.

The 2016 Alberta Labour Force Profile of Indigenous People finds that about half of employed Indigenous people living off-reserve in Alberta work in four industries: construction (15.9%), retail trade (11.9%;), health care and social assistance (11.7%), and forestry, fishing, mining, and oil and gas (8.7%).

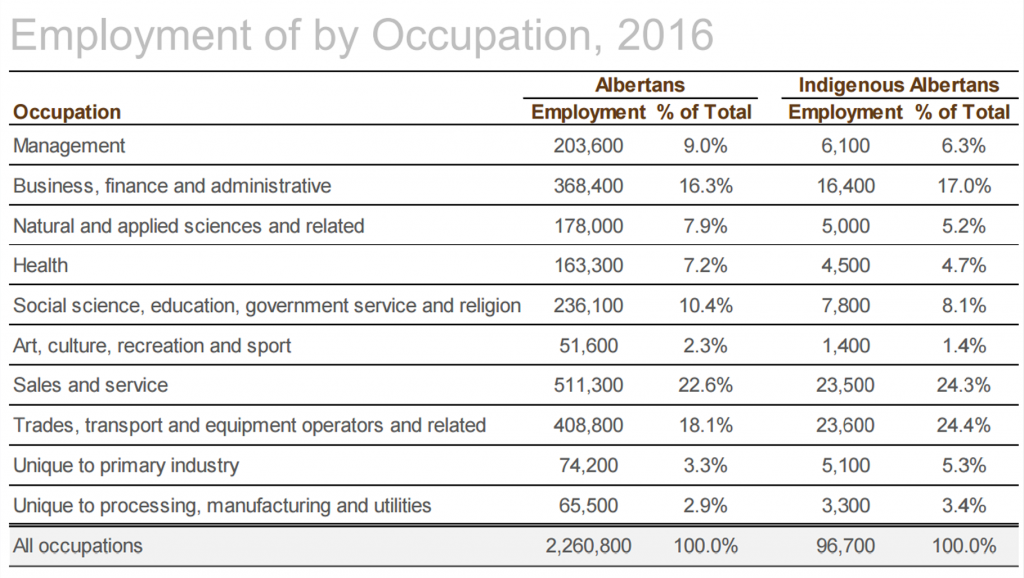

The profile also shows there are five occupational groups that Indigenous people living off-reserve occupy at higher rates compared to the Alberta population in general.

Image source: 2016 Alberta Labour Force Profile of Indigenous People

Compared to 63.2% of the general Alberta population, almost 74.4% of Alberta Indigenous people in 2016 worked in:

- Business, finance, and administration (Indigenous 17%; Alberta 16.3%)

- Sales and service (Indigenous 24.3%; Alberta 22.6%)

- Trades, transport, and equipment operators and related occupations (Indigenous 24.4%; Alberta 18.1%)

- Unique to primary industry (Indigenous 5.3%; Alberta 3.3%)

- Unique to processing, manufacturing and utilities (Indigenous 3.4%; Alberta 2.9%)

10. The Treaty Alliance Against New Pipeline Development is a major new initiative in the longstanding opposition to Alberta oil sands development

The Treaty Alliance Against New Pipeline Development was signed in September 2016 and commits over 50 First Nations and Tribes from Canada and the United States to work together to stop proposed oil sands pipeline, tanker, and rail projects on their lands and waters.

In an effort to promote a more sustainable and equitable future and in the context of a resurgence in Indigenous sovereignty, these Nations and Tribes are uniting as caretakers of the land and water to oppose these oil industry projects.

The Treaty includes bans on the following pipelines specifically, which if built would lead to significant growth of oil sands production:

- Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion

- TransCanada’s Energy East Pipeline

- TransCanada’s Keystone XL Pipeline

- Enbridge’s Northern Gateway Pipeline

- Enbridge’s Line 3 Pipeline

In January, multiple First Nations launched legal challenges to the newly approved Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion project. The court challenges are based on claims of inadequate consultation and the risk to water in nearby communities. Chief Lee Spahan of Coldwater said, “For Coldwater, this is about our drinking water. It is our Standing Rock.”

Conclusion

These 10 items are only some of the important things to be mindful of as we begin to understand the complex relationship that Indigenous people have with the state and with resource development in Alberta and elsewhere. Educating ourselves on the complex relationships between Indigenous and settler peoples, communities, and the state is an important step towards meaningful reconciliation, and an effort we must continually engage in.

Many Indigenous peoples and communities are connected to the resource extraction industry in numerous and complex ways—further complicating this is the long history of colonialism that shapes the relationship between people and the state. Moving forward, governments, industry, and settler populations need to appreciate the fundamental differences between dominant Western knowledge and forms of Indigenous knowledge which can further complicate these relationships. With Indigenous youth being the fastest growing population in the province, Alberta’s future will be tied to this population. However, with education and career pathways for this population currently limited, Alberta needs to appropriately invest in Indigenous youth to support their future.

Ongoing and new industry developments need to do more to engage with and respect Indigenous peoples. The current practice of impact assessments is proving to be inadequate, and public-private partnerships are similarly problematic. Indigenous peoples are increasingly working together to oppose developments that negatively impact them through efforts such as the Treaty Alliance Against New Pipeline Development.

Finally, a fact that needs to shape these discussions going forward is that we are all treaty people living on land that must be understood through these agreements.

While the information shared in this blog is based on research, it is important to note that much past research on Indigenous people was not done in the spirit of equality, respect, and meaningful engagement. Unfortunately, some current research continues this colonial knowledge relationship. Best efforts have been made in researching this piece to ensure Indigenous perspectives are prioritized and placed at the centre of the issues.

When we hear the government of Alberta discussing First Nations and Métis relations in a nation-to-nation context, we observe efforts to move forward in the spirit of equity and respect. However, it is important that we continue to monitor these issues to ensure encouraging words are more than just rhetoric, and are followed up with action rooted in the same spirit of mutual recognition, reconciliation, and respect.

This post was produced as part of the Corporate Mapping Project (CMP). The CMP is a six-year research and public engagement initiative jointly led by the University of Victoria, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ BC and Saskatchewan Offices, and the Alberta-based Parkland Institute. The CMP is supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Author: Angele Alook, Nicole Hill & Ian Hussey

Dr. Angele Alook is a proud member of Bigstone Cree Nation and a speaker of the Cree language. She recently successfully defended her PhD in sociology from York University. Her dissertation is entitled “Indigenous Life Courses: Racialized Gendered Life Scripts and Cultural Identities of Resistance and Resilience.” She specializes in Indigenous feminism, life course approach, Indigenous research methodologies, cultural identity, and sociology of family and work. Angele currently works in the labour movement as a full-time researcher for the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees. She is also a co-investigator on the SSHRC-funded Corporate Mapping Project, where she is carrying out research with Parkland Institute on Indigenous experiences in Alberta’s oil industry and its gendered impact on working families.

Ian Hussey is a research manager at Parkland Institute. He is also a steering committee member and the Alberta research manager for the SSHRCC-funded Corporate Mapping Project.

Nicole Hill is a PhD student in the sociology department at the University of Alberta and she was a research assistant from 2016 to 2018 at Parkland Institute. She is a graduate of Athabasca University’s Masters of Arts in Integrated Studies program, where she focused on equity studies. Nicole’s current research is on maternity care experiences.