The BC Utilities Commission (BCUC) inquiry into gas prices delivered its bombshell final report on August 30. Among its key findings: at least 13 cents per litre of the higher gas prices at the pump over the past couple years is “unexplained” relative to what one would expect from a functioning competitive market. This is a polite way of saying gouging by oil companies has been rampant, at an estimated cost of about half a billion dollars per year out of drivers’ pockets, BC-wide.

The BCUC broadly supports the analysis first offered up by myself (and independently by Michael Wolinetz of Navius Research) in June 2018 and then again in April 2019 when prices really got out of hand. We were able to use gas price data, which break down pump prices into four core components: the price of crude oil; the margin going to refineries that convert that crude into refined fuel products like gasoline and diesel; the retail margin going to gas station operators; and taxes paid to federal, provincial and regional governments.

The X factor in this analysis is the dramatic increase in refining margins for gasoline (but not diesel), which have surged relative to Vancouver’s own history, to other Canadian cities and to our US neighbour, Seattle. To a lesser extent, higher retail margins were also a source of growing gas price differentials. From the Vancouver perspective this looks like either market manipulation or market failure that needs to be remedied through public policy such as price regulation introduced in the Maritime provinces. My colleague David Hughes added another key point that flows of refined products to the Vancouver market on the Trans Mountain Pipeline (TMP) had been dramatically curtailed in recent years.

We argued that oil companies had a lot of explaining to do and that arguments that this was “just supply and demand” were not sufficient. The BC government clearly agreed and launched the BCUC inquiry in late May, which took submissions and put oil companies and other experts on the stand. The BCUC final report pries open somewhat the black box that is the oil industry—although some details were never provided to the BCUC, while others were shared only under strict confidentiality. Nonetheless, the BCUC closely examined the claims made by the industry (and their gas buddies) to justify those high prices and found them lacking.

Interestingly, just three weeks after the announcement of the inquiry, pump prices fell by 22 cents per litre and remained fairly stable through the summer. It is as if the companies realized that they were about to come under scrutiny and sought to mitigate public outrage with lower prices. But with price hikes before the Labour Day weekend and after drone attacks in Saudi Arabia, we need public policy to prevent price gouging in BC. And while it’s true that high prices are a good thing from an environmental and climate perspective, the key point is that any excess should flow to building the clean economy we want, not to lining the pockets of oil industry shareholders.

Unfortunately, the BCUC report came out the Friday afternoon before Labour Day weekend so media attention was not as widespread as it should have been and some of the media coverage got the story wrong. I have reviewed the main findings of the report with a focus on Vancouver and the South Coast and taken a look at next steps to prevent future gouging. There is a 30-day comment window on the final report, so readers should consider making their own submissions to the BCUC about what comes next.

Market power along the gas supply chain

The demand for gasoline in Vancouver and BC overall is fairly stable. While population has been increasing, this has been offset by a modest shift away from driving to other modes like transit along with more fuel-efficient vehicles including all-electric and hybrids. Given fairly steady gasoline consumption, it should not be too difficult for a small number of suppliers to meet that demand and earn a reasonable profit without gouging consumers.

The inquiry notes that 90% of the South Coast market for gasoline is controlled by four companies (Parkland, Suncor, Imperial and Shell). Only the Parkland refinery in Burnaby produces gasoline locally for the Vancouver market, with the difference largely sourced from Edmonton refineries via the TMP plus some imports from the US. This is somewhat complicated by the fact that the big oil companies have integrated operations spanning crude production, refining, marketing and retailing, to greater and lesser extents.

There is no evidence these companies have historically had a problem supplying the Vancouver region at prices consistent with other cities, and nothing has fundamentally changed in recent years in terms of the underlying infrastructure of oil wells, refineries and pipelines. Oil producers and refiners have fairly fixed cost structures due to large capital investments made in the past. So there is no good reason why gas prices at the pump should fluctuate so wildly from month to month or even day to day.

The BCUC examined explanations from oil companies about higher costs of getting gas to market, but even after a generous accounting of these costs there remained that “unexplained” gap of 13 cents per litre for wholesale prices (that is, the price of gas sold by refineries) over the past couple years and that did not exist at all prior to 2015. Due to measurement issues, the BCUC had a harder time pinning down a value for higher retail margins in Vancouver, but did conclude that they are much higher than elsewhere.

Critics of the inquiry have argued that examining higher costs from taxes and regulations should have been part of the terms of reference. In the case of taxes, there’s not much to see here: compared to 2015, higher fuel and carbon taxes explain about five cents per litre of the total increase in pump prices. In terms of BC’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), the BCUC overstepped its mandate and went ahead and assessed the impact, since this was raised by oil companies. The Panel found that the LCFS accounted for at most four cents per litre of the difference between BC gas prices and elsewhere.

As for the 13 cents per litre unexplained difference, it would appear that gas price gouging in the absence of meaningful competition is the most plausible explanation. Why wouldn’t a company seek to increase its profits by raising prices if it could? Moreover, the timing of those increases allowed some to blame them on higher carbon taxes (which did increase in April but by only one cent per litre) and to argue just before the deadline for federal approval of the controversial Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion (TMX) Project that the expansion was needed to alleviate this situation.

Consider it a winning trifecta for the industry: boost profits, shift blame to the carbon tax and make the case for TMX.

On this front we can point to Parkland’s regular reports to its shareholders bragging about its latest financial results. Parkland’s 2018 annual report attributes $400 million in increased earnings to the acquisition of the Parkland refinery, and its recently released second quarter 2019 report puts earnings from the Burnaby refinery at $359 million for the first half of the year.1 For the other larger oil companies it is hard to break out profits from their full operations and this is one area that did not get any attention from the BCUC.

Common media narratives debunked

As prices shot up earlier this year, media commentary cited explanations not from the industry but primarily from one analyst, former federal politician Dan McTeague, who made claims that refinery downtime and substantial imports of more expensive gasoline from Washington state refineries, plus high taxes were the cause of high prices, and that TMX was the solution. Last year, McTeague was cited stating that 25% of Vancouver’s gas comes from four refineries south of the border, and in another article at the time of peak prices earlier in 2019, that 30–40% of gas supply is met from those sources.

In contrast, the inquiry found that only 3% of total sales came from Washington state. McTeague may have been misquoted, but his arguments appeared to justify ongoing gouging by the industry. While an unplanned outage could potentially affect the price of that small amount of imported fuel, for the most part refinery downtime happens routinely and the industry plans accordingly to maintain adequate supplies that they are contracted to provide to retail outlets.

The main economic argument for higher prices has been that supposedly higher-cost US imports, called the “marginal barrel” of gasoline, were setting the price in Vancouver. That is, companies were not gouging, just the fortunate beneficiaries of the marketplace. This argument assumes some external independent supplier coming in to provide this higher cost supply, whereas the panel found that all of the companies were importing fuel to some extent. This may slightly increase their average costs, but using 3% of imports to hike prices on the other 97% produced in Canada was, in the Panel’s opinion, a stretch.

The Panel concludes:

Although supply from the PNW [Pacific Northwest] constitute only about 3 percent of BC’s total imports, the unexplained differential of approximately 13 cpl [cents per litre] applies to all wholesale gasoline sold in southern BC. Given the differential of 13 cpl in southern BC and 6 cpl in northern BC we estimate that applying an average 10 cpl differential to all gasoline sold in BC consumers paid approximately $490 million per year more than they otherwise would have paid.

What about the Trans Mountain Pipeline?

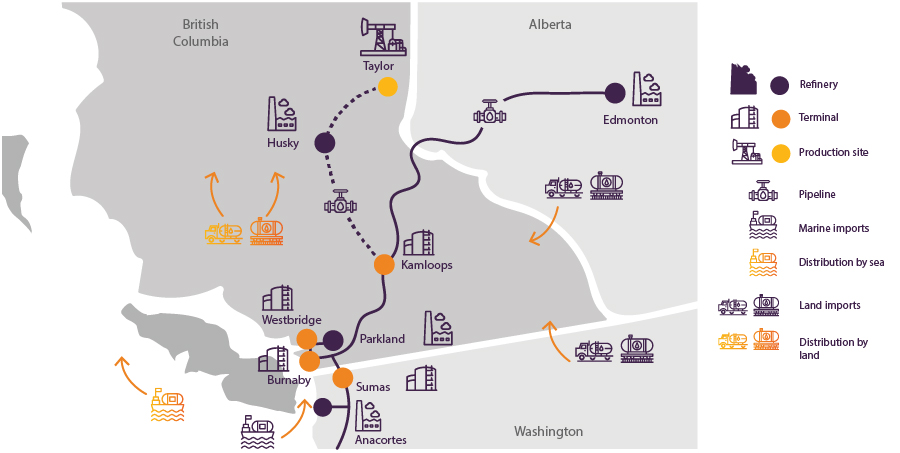

The Trans Mountain Pipeline, now owned by the federal government, delivers crude oil to Parkland’s Burnaby refinery for processing into refined fuel products, and also delivers refined fuels from Edmonton refineries to Metro Vancouver. Most of its capacity, however, is used to export crude to Washington state refineries via the Puget Sound pipeline connection at Sumas, with additional exports by tanker via the Westridge dock in Burnaby.

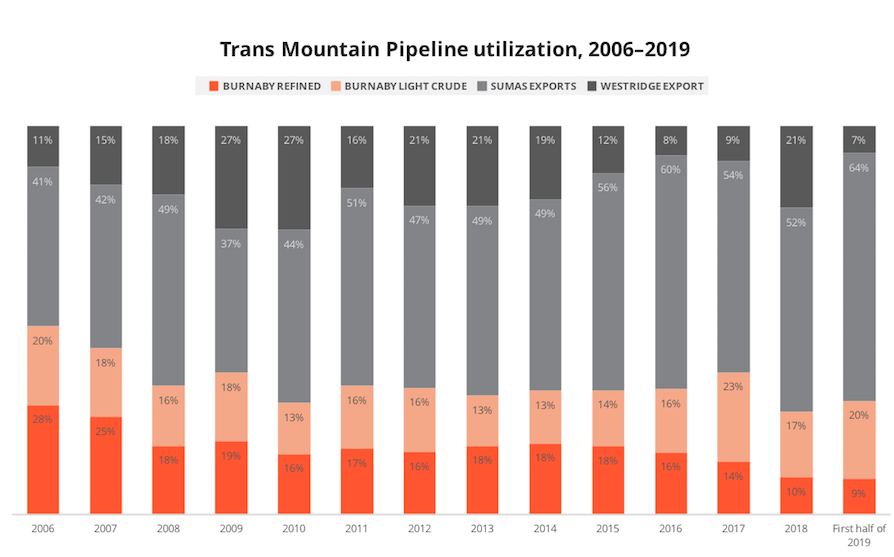

National Energy Board (now the Canada Energy Regulator) data on the TMP show a decline of refined fuels from Edmonton refineries. In 2018, refined fuels going to Burnaby fell to 10% of the total, and 9% in the first half of 2019, both much lower than any other time in recent history. Crude oil going to the Parkland refinery in Burnaby is consistent with past years (there is a bump up in 2017 as inventory was being accumulated in advance of a major refinery turnaround at the start of 2018).

These data show that capacity of the existing TMP per se is not the problem. More than half of pipeline capacity (and 64% in the first half of 2019) was used for crude oil sent to Washington state refineries and additional exports by tanker were made via the Westridge terminal in Burnaby. Combined, some 73% of the TMP was allocated to exports in 2018, and 71% in the first half of 2019. Going back to 2006, in only one other year (2010) did the share of TMP going to exports exceed 70%.

The BCUC concluded that as Alberta production increased it led a glut of oil and lower prices for Alberta crude relative to other jurisdictions. This created an arbitrage opportunity that made it more profitable to ship crude oil for export than refined fuels needed for Vancouver drivers. In other words, crude exports have been crowding out gasoline on the TMP. The local gas shortfall has been made up from shipments by rail and barge, both of which add additional transportation costs, but again these costs are not sufficient to explain gasoline price differences.

Another piece of the puzzle is the method used to allocate space on the TMP, which adversely affects the supply of refined fuel products coming into Metro Vancouver and the South Coast.

TMP allocation procedures introduced in 2015 favour Washington refineries. The National Energy Board agreed with this in a March 2019 note to the federal Minister of Natural Resources, stating that “existing verification procedures across the industry as a whole allow shippers to nominate more oil to pipelines than can be supplied. Integrated producers and those shippers that own or have contracted crude oil storage and refinery capacity have a greater ability to acquire pipeline capacity.”

Time for regulation

Bottom line, the supply of gasoline to Vancouver is far from a textbook model of a perfectly competitive market, although several commentators have been falsely seduced by that notion. To recap, the BCUC summarizes:

In general terms, in the sections above the Panel found that the wholesale market is oligopolistic, with high market concentration levels, high barriers to entry, and the few players can exercise market power. When comparing the Vancouver rack price to the PNW [Pacific Northwest] spot, the Panel finds that a large portion of the price differential in recent years cannot be explained using quantifiable cost factors. The lack of access to primary terminals by any entity other than one of the Oil Companies is also a key choke point. While the retail market is less concentrated, the Panel cautions that the higher than Canadian average of refiner-marketers participating in the retail market may still have an impact on being a fully competitive market. In addition, the Panel finds that retail margins in BC are higher than they are in the rest of Canada.

When markets do not perform as they should, there is a strong case to be made for regulation to better align their operations with the public good. BC’s next move should be regulatory reform to put a lid on gouging behaviour, stabilize prices for consumers and make the industry more transparent to all concerned. Companies should not be able to jack up prices whenever a convenient excuse to do so comes along.

Price regulation

The BC Utilities Commission already regulates electricity and natural gas prices. Its mandate should be extended to gasoline. Even the annoying up-and-down swings of gas prices in Metro Vancouver on a weekly basis could be tamed by a more regulated market. BC should take a page from the Maritime provinces, all of which regulate the maximum price of gasoline at the pump. When prices peaked last April Halifax gas prices (excluding taxes) were about 30 cents per litre cheaper than in Vancouver.

The BCUC suggests that regulation at the wholesale level would make more sense as there is more competition at the retail level. Indeed, a better regulatory framework could make the retail side more price competitive and this could also include measures (like access to storage terminals) that better allow other companies to compete in this market on a more level footing.

More transparency and accountability of refinery data

The BCUC report points to other jurisdictions like California, Hawaii and Washington state, each of which has much more stringent reporting requirements about production volumes, transportation flows, inventory levels and so forth. Companies responded that this is commercially sensitive information, but those arguments should be shunted aside in favour of a more transparent marketplace.

According to the NEB, there are substantial gaps in publicly available data that would make markets function more effectively:

Additional data could help market participants in a variety of ways. For example, if small producers knew storage was almost completely full or that refineries were shut down, then they could anticipate not being able to sell or store their product, and might decide to reduce production. Data regarding refinery crude runs and refinery outages would also be beneficial for most market participants for planning purposes. More detailed apportionment data would help producers better understand the volume of oil being “pushed back” to them by apportioned shippers.

Provinces regulate their energy infrastructure and could require reporting for various levels of storage, from field level to hub level.

Ensuring supply on the existing Trans Mountain Pipeline

We need to ensure that refined fuel products from Alberta can be set aside as “committed shipments” and make it to Metro Vancouver and the BC South Coast rather than the region having to compete with exports for space on the TMP. Interestingly, the Westridge Terminal in Burnaby has committed supply, but only for export.

The federal government, as owner and regulator of the TMP, should step in to change the allocation rules such that Vancouver demand for fuel would be satisfied by domestic sources. This is of national interest as it does not make sense for Canada to export crude to US refineries so that we can import refined products that could be sourced from Alberta refineries.

Claims that only the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion can solve Vancouver’s high gas prices ignore the vast amount of exports currently using up the majority of space on the existing pipeline. Whether the TMX would alleviate these problems cannot be guaranteed since the new pipeline is aimed squarely at supporting crude exports. The TMX application to the NEB says nothing about ensuring more refined fuel supply to Vancouver and as the BCUC report notes, plans for TMX do not include any additional terminal capacity for refined products.

Final thoughts

Thanks to the BC government for launching this inquiry and to the BCUC for thoroughly engaging the topic in lieu of summer vacation. The situation with regard to gasoline prices is extreme—it’s hard to name any other market where the price is so volatile from week to week and over the course of a year. The BCUC inquiry was much needed because the oil industry is so opaque in terms of available data and information. In some ways there is much more the BCUC could have uncovered for public consumption, but its work gives British Columbians a much more coherent picture of how the industry operates and why prices surged to such highs.

All of this work will be for naught if the BC government does not step in to compel companies to stop gouging behaviour. Some form of price regulation would be advised to tame this market. And with a federal election on, candidates should be asked about making more refined fuel available through the existing, federally owned TMP.

1. “Earnings” here are “earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization,” or EBITDA, as used in the financial reports.

Author: Marc Lee

Marc Lee is a Senior Economist at the CCPA’s BC Office and a co-investigator with the Corporate Mapping Project (CMP).

In addition to tracking federal and provincial budgets and economic trends, Marc has published on a range of topics from poverty and inequality to globalization and international trade to public services and regulation. Marc is Co-Director of the Climate Justice Project, a research partnership with UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning that examines the links between climate change policies and social justice.